EN / ID

The New East Indies:

A Manifesto for Creators

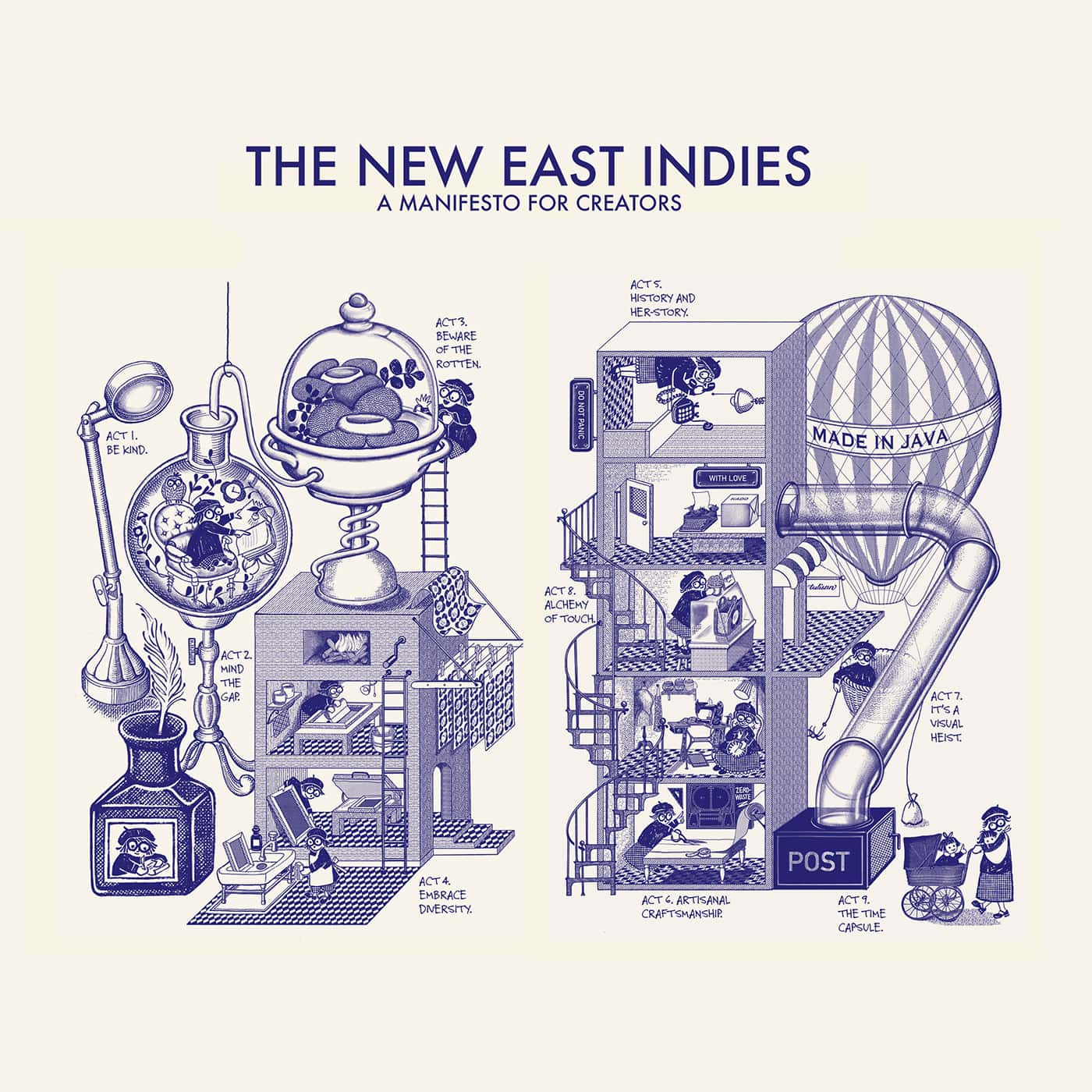

by Melissa SunjayaAn open invitation and guiding framework for creators from diverse backgrounds to reinterpret history as a shared story.

The New East Indies Manifesto offers an unconventional lens on Southeast Asian history, as well as questioning social order and cultural values.

The term ‘East Indies’, coined by Europeans for the archipelago, first appeared on 16th-century navigational maps. Long before formal colonisation, ports in Java had developed as trans-oceanic trading hubs. Here multicultural communities lived harmoniously.

Understanding the present requires returning to an era when the Netherlands Indies colonial state (1816-1942) began dismantling bodies of local knowledge. These encompassed naval, architectural, literary, artisanal, matriarchal, and communal legacies.

Centuries of systemic plunder did not exhaust the islands’ abundance, yet epistemic silencing continues to shape our self-perception, and an orientalist lens still distort our gaze. The New East Indies pursues imaginative vocabularies of discourse that identify missing links in inherited values, thus removing feelings of inferiority. The adjective ‘New’ signals an alternative present in which we consciously cultivate the earth, celebrate authenticity, and cherish one another. By forging new memories,we invite these possibilities to empower our lives.

Indonesia’s proclamation of independence on 17 August 1945 closed 350 years of the Dutch presence in the archipelago, of which the last century and more had left a prevalent sense of inadequacy. Our present-day polarised communities, corruption, ecological exploitation, racism, and fragile infrastructure mirror the struggles of nineteenth-century Java. History thus serves as a compass. It reveals borrowed fragments of identity, warns against repetition of the past and urges critical self-examination. This is particularly the case with the image we broadcast to the world. More importantly, it also questions the self-portrait we impose upon ourselves.

Decolonisation is radical self-preservation. It is an active process of finding our roots and discovering our forgotten identity through fragments of history, tradition, and mythology. Doing so can be a daunting journey requiring us to confront our inner monsters.

Scope of Inquiry

Throughout this manifesto, the word ‘artist’ denotes any practitioner who writes, draws, paints, dances, films, animates, prints, sews, designs, creates, or builds while upholding sustainable principles. An artist of the New East Indies seeks to renew appreciation for the region’s own history and mythology by employing a poststructuralist lens to enable seeing familiar things in unconventional ways. Such a lens opens a field of almost boundless possibility. It often induces a deliberate and surreal sense of temporal dislocation. Within this framework, every act of storytelling must keep in view the horizon of decolonisation.

The following guiding precepts are essential:

Act 1.

Be Kind

Kindness is a skill to be cultivated through multiple perspectives. An artist understands that probing past realities can evoke discomfort, intimidation, and even pain. Conveying such realities to an audience unfamiliar with these intricate histories is even more demanding.

Gillian Rose’s framework of visual methodologies offers a compass for responsible practice. Such methodologies invite us to examine the circumstances of an image’s production. In so doing we can attend to its internal composition, trace its trajectories of circulation, and study the spaces where the artwork meets its viewers. Through such an approach, an artist nurtures empathy while advancing the process of internal decolonisation.

Act 2.

Mind the Gap

An artist must reexamine the continuing influence of colonialism in modern capitalist guise, even though its author(s) have long departed.

Over time it became a fundamental part of the Western academic field and knowledge production. Colonialists eliminated valuable Southeast Asian knowledge, traditions, and cultures. They viewed these elements as conflicting, of inferior quality, or incoherent.

Additionally, many artefacts were looted during colonialism. This was the case during the British invasion of Java (1811-1816) when a vast quantity of data was collected at the order of Thomas Stamford Raffles and his associates. The artist’s first task is therefore restorative: rebuild the censored, rescue the overlooked. Visual references are scarce on certain subjects such as the near vanished world of Javanese matriarchy and female lineages. Thus, an artist must find links between records or events that occurred in different places and around the time of that subject. They then need to be rewoven into a living tapestry.

Act 3.

Beware of the Rotten

An artist must look out for irrelevant values to create regenerative designs which promote equality.

Colonial influence often hides inside everyday habits and standardised knowledge. This slows down progressive thought. Lévi-Strauss’s culinary triangle clarifies this task: the raw is our material, the cooked is our craft, the rotten is what demands regeneration (Sennett 2019: 119–46). Rot appears as bias, stigma, or stale belief. With the same raw elements the artist can imagine an alternate reality.

Consider the Dutch sign that once warned, ‘Niet Voor Honden en Voor Inlanders!’ [‘Not for Dogs and Natives!’], banning Javanese banning Javanese from their own parks.97 The boards fell in 1945, yet subtler barriers remain. Colonial houses placed Dutch owners in the front and servants in the rear; a structure that served to separate Dutch homeowners from their native household staff. Today, the terms ‘depan’ [front] and ‘belakang’ [back] – the equivalent of ‘upstairs-downstairs’ in 19th-century Britain – are still used to differentiate the residents who own a property from the housekeeping staff who work there. These systemic labels preserve colonial social injustices. These comprise unfair working conditions, differences in food quality, and financial compensation far below the official state-determined minimum wage. An artist may reverse this plan by reconstructing residential space responsibly. Such acts invite inclusivity.

Act 4.

Embrace Diversity

As the world becomes increasingly multicultural and borderless, art must embrace diversity. Southeast Asia, a region of hugely diverse ethnicities, embodies this call.

Honouring the fifth rule of the Fashion Revolution Manifesto,an artist has a duty to ensure that their work upholds the principles of solidarity, inclusiveness, and fairness. This must be done regardless of race, class, gender, age, shape and ability.

Art is for everyone. Accessibility to art opens doors to research. This includes the use of historical graphic novels or sign language for storytelling. Image-making draws on dances, music, textiles, games, folklore, food, and the living flora and fauna of the region. The artist collaborates with marginalised makers. Insight is deepened through collective work with scientists, historians, philosophers, and anthropologists to foster economic resilience, environmental responsibility, and cultural preservation. Difference is not merely tolerated, but valued as a necessary dialectic space where creativity is sparked.

Our focus is on expanding a circular economy model, bridging art, sustainability, and community empowerment—one that aligns with solidarity-based economies, where wealth is redistributed to those who create value rather than concentrated in large corporations.

By sharing infrastructure, knowledge, and ethical production systems, our aim to build a self-sustaining creative ecosystem where artisans receive fair wages, access to resources, and long-term economic security.

Act 5.

History and Her-story

An artist must bring forward the neglected heroines of Southeast Asian history. Pre-colonial Javanese culture maintained a balance between patriarchal and matriarchal power; women shaped politics, trade, and war.

Dutch colonial writers later recast these female figures as exotic, obedient, sensuous and mute, erasing their authority. Consider Kartini (1879–1904), who had to endure a long ‘pingitan’— self-isolation at her residence from the first day of her first menstrual cycle in 1891 until her wedding day twelve years later. Traditionally, during this isolation period, a female royal learned patriarchal values and prepared for her betrothal to the male suitor who met the requirements and bridewealth set by her family. Kartini refused silence: she read widely, wrote incessantly,and recorded the hopes of a generation. Yet contemporary novels, films, and social feeds still promote the demure Javanese woman as the ideal.

Our duty as artists is to overturn such myths and portray women with the strength and agency which history once imbued them with in the pre-colonial era. It is time to let their full light shine.

Act 6.

Artisanal Craftsmanship

The artist begins with the material and the mark it leaves on the earth. This consciousness must drive us constantly to evaluate our options and strive for sustainability. This enables the metamorphosis of our material choices. What we consider ethical and environmentally friendly today may not be so tomorrow.

Our duty is to keep the creative hand alive and honour its beautiful imperfection. Textiles can become pages for new stories; fibres can hold stories the way paper does. We can also invite post-human tools into the studio—letting generative systems extend touch and sight, helping to conserve and re-imagine older forms in new guise. In this weave of tradition and technology,

craft endures, breathes, and begins anew.

Act 7.

It’s a Visual Heist

An artist employs visual transcription as a tactic of taking established cultural texts and rewriting them through personal and local lenses. This approach to reinterpreting colonial-era visual archives and traditional crafts through modern functional designs and contemporary expressions mirrors this form of cultural re-appropriation and resistance.

Through reappropriation, Kenneth Goldsmith challenged the notion of originality in art. He underscored how all creative work builds upon that which came before.Why reappropriate? Many forms of appropriation occurred in the post-colonial period. For example, ‘blasteran’ is Indonesian slang for a biracial person. The term is derived from ‘bastaard’, the Dutch word for bastard. Since colonialism, biracial citizens have been marginalised. Thus the process of reappropriating ‘blasteran’ can have positive outcomes. Such outcomes can pulverise disparaging meanings. Hence, decolonisation may begin with literary reappropriation.

As artists, we transcribe visual remnants from the past to reclaim, reassemble, and resignify a new sense of entitlement. In so doing, we build a more hopeful vision of the New East Indies. Using the CC0 or Creative Commons License 0 from world-trusted data banks such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Rijksmuseum, the British Library, and the Leiden University Libraries, we can construct a new paradigm for our Southeast Asian cultural identities. The act of visual reappropriation is not visual theft. Instead, it is a careful curation of renowned archived CC0 articles with proper credit given to all sources. This is done to recontextualise maligned subjects, imbuing them with entirely new attributes. The positive can then replace the negative. The starting point here involves listening, understanding, and learning about dialectic perspectives. Other cultures need to be brought into the frame. We can then begin to connect cross-culturally and mend our differences. In turn, reappropriation must inspire honest and open discussion. Only thus can we begin to decolonise our minds.

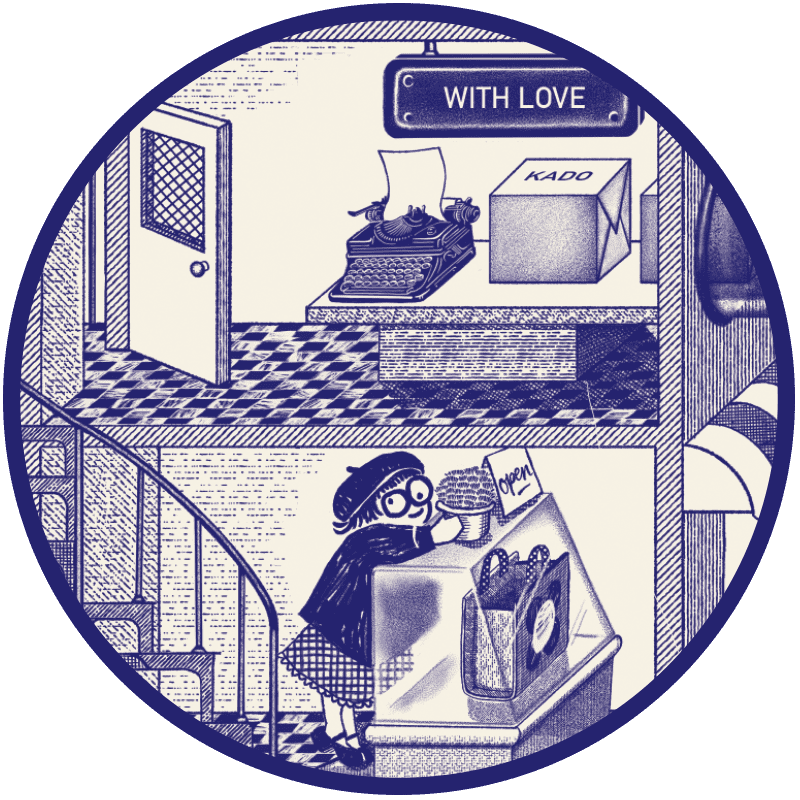

Act 8.

Alchemy of Touch

Through layers of domain shifts an artist moves through various stages. We must begin by appreciating culture and understanding our respective histories.

Only by acknowledging and healing our inherited traumas can we begin to shape new realities. We can then recontextualise image making, redefine semiotic relations, and design future artefacts. In this way, we can build experiential exhibit spaces.

We establish our presence as creative artists by building our visual lexicons. This involves depicting empowering metaphors of our surroundings, and creating anchorage through colours and signs. This is the New East Indies’ methodology: listening, reading, seeing, making, and learning.

The artist’s canon encompasses a mixture of visual markings and memory tracing experiments involving imagination, observation, and interpretation (Freud 1925). Freud’s theory of memory suggests that human beings are unconsciously influenced and biased in their perceptions. Therefore, our visual and/or literary responses are never free from bias. All too often they have become the dominant influence in our creative lives.

In the digital age, it has become all too easy to adopt manipulative and polarised opinions especially, since digital culture excludes the sense of touch. Therefore, analog experiences and the study of touch remain essential tools in an artist’s work for reconstructing positive memories and reconnecting with our senses. In many neurological behaviour cases, generating optimistic memories can encourage epigenetic changes in our human bodies and quicken healing powers to resolve our traumas.

Act 9.

The Time Capsule

Through wearable artefacts, an artist treats textiles as a moving canvas, an interactive form of storytelling that allows Javanese history to be worn, carried, and shared in contemporary and pragmatic settings.

This method challenges the traditional notion of art as a static medium, transforming it into a living, participatory experience. It also reconnects with Java’s indigenous traditions of visual storytelling from the female perspective, where objects carry spiritual and historical significance. During our pre-colonial history, women in Java and the surrounding islands have held influential roles as guardians of nature and ancestral stories through weaving and batik painting. Our aim is to preserve this tradition—one created by Javanese hands, for Javanese voices.

Marking an object can be a political act of establishing one’s presence and self-actualisation. The wearable artefacts will function as the ultimate storytelling platform, demonstrating the artist’s reflexivity in terms of cultural context and constituting a dignified paradigm of artisanal craftsmanship. The artefacts will encapsulate the maker’s mark.

These may take the form of gifts, letters, statements, or simply as adornments. The mobility and functionality of these artefacts on human bodies will eventually serve as the hallmark of an empowering culture. It will cast wide open doors, inviting those who once felt cast out to belong to a new multicultural society—regardless of race, class, gender, age, shape, or ability.

Melissa Sunjaya

Artist.