EN / ID

Chapter I.

Simpang Masa

Prince Diponegoro is an iconic figure in modern Indonesian history, embodying resistance and vision against Dutch colonial rule. Beyond armed struggle, his autobiography reveals intimate reflections on a world in transition between old Java and the colonial Indies, inviting us to reconsider identity, history, and Indonesia’s authentic future.

![Prince Diponegoro is an iconic figure in modern Indonesian history, embodying resistance and vision against Dutch colonial rule.]()

Who are we today, who were we then, and what will we be? During the pandemic I lost loved ones and faced deep fear—fear of collapse, conflict, and a fragile planet. One sleepless night, my longing for freedom from this fear led me back to Java in 1830. As a Western-educated Javanese woman shaped by European culture, I realised I had never fully embraced my Javanese identity. Discovering Prince Diponegoro’s integrity set me free. I hope his story may also guide you.

—Melissa Sunjaya

Through many extraordinary events, fate appointed me—a non-Javanese—as Prince Diponegoro’s modern biographer. He was not a perfect man, yet his integrity and self-sacrifice still speak directly to us today. If we are willing to listen, his life can teach us much about who we are and who we might become. A touchstone for the modern world, he transformed my life and Melissa’s. Together, we offer 1830 to the world.

—Peter CareyWho Was Prince Diponegoro?

Born in Yogyakarta on 11 November 1785, Diponegoro was the eldest son of Sultan Hamengkubuwono III. Though he was born to courtly privilege, the fates dictated that he would be brought up instead to a life of spiritual discipline, political integrity, and service to his people. His life and times eventually became one of the most significant turning points in Javanese and Indonesian history.

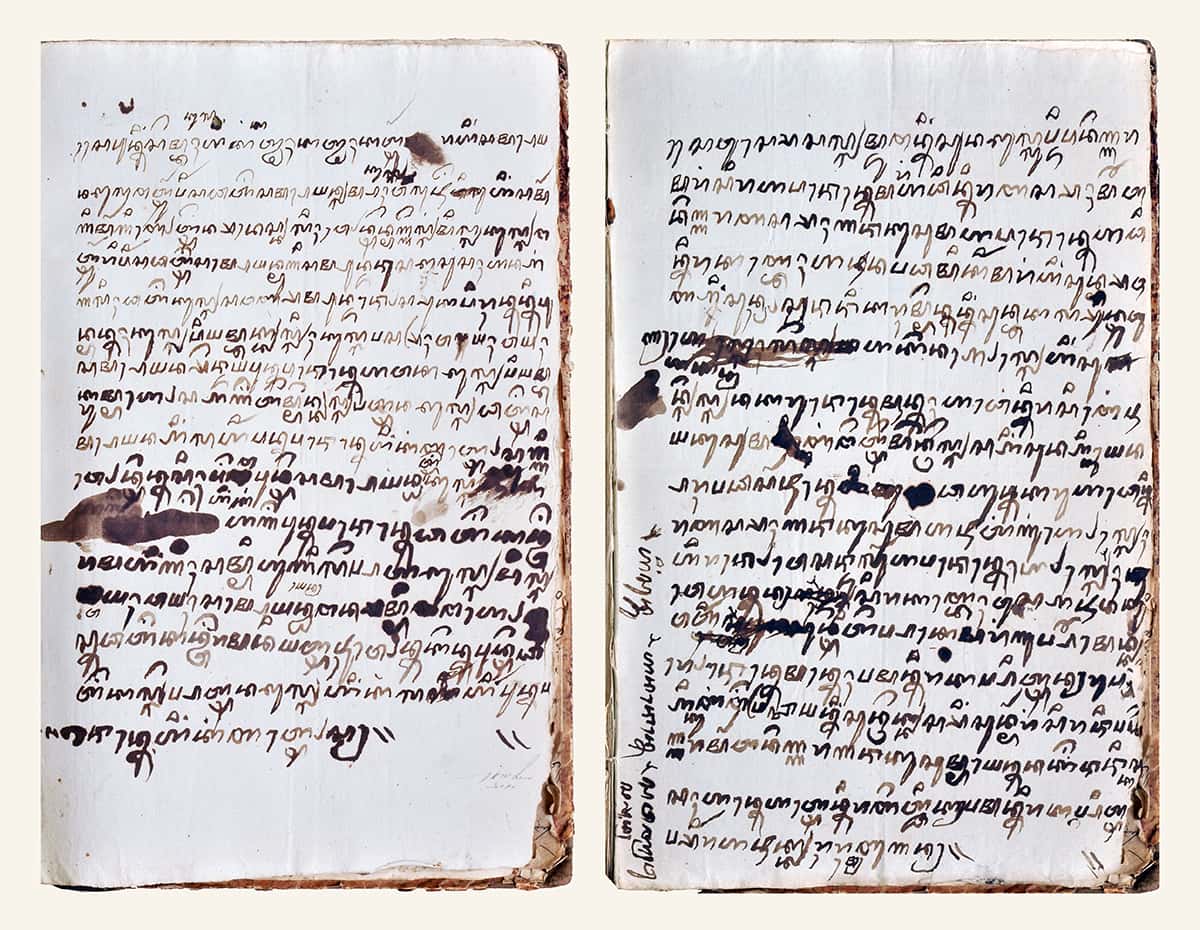

Diponegoro’s reputation rests not only on his leadership of the Java War (1825–1830) but also on his writings, particularly his Babad Diponegoro, often regarded as the first modern Indonesian autobiography. In this text, he outlined his ideals of good governance, tolerance, and moral order. His resistance was never just about reclaiming land and material assets; it was about restoring dignity and creating a vision of justice. His steadfast integrity continues to provide insight into the struggles of his time and their relevance to ours.

Between Two Worlds: Simpang Masa

Diponegoro’s life unfolded at a threshold moment—what might be called simpang masa—between pre-colonial Java and colonial Java. This change was also reflected in world history with the industrial and political revolutions reshaping Europe. The Java War of 1825–1830 marked this rupture. Before the war, Java retained many of its traditional structures and belief systems, despite growing European influence. After the war, Dutch control became complete, reshaping politics, economy, and culture.

This transitional moment resonates with the present. Two hundred years later, Indonesians again stand at a crossroads, facing rapid globalisation, deepening inequalities, and the challenges of climate change. Just as Diponegoro grappled with the forces of his age, today’s generation must navigate how to balance heritage and progress, rootedness and openness. His life serves as a mirror for considering how to live meaningfully during a time of transition.

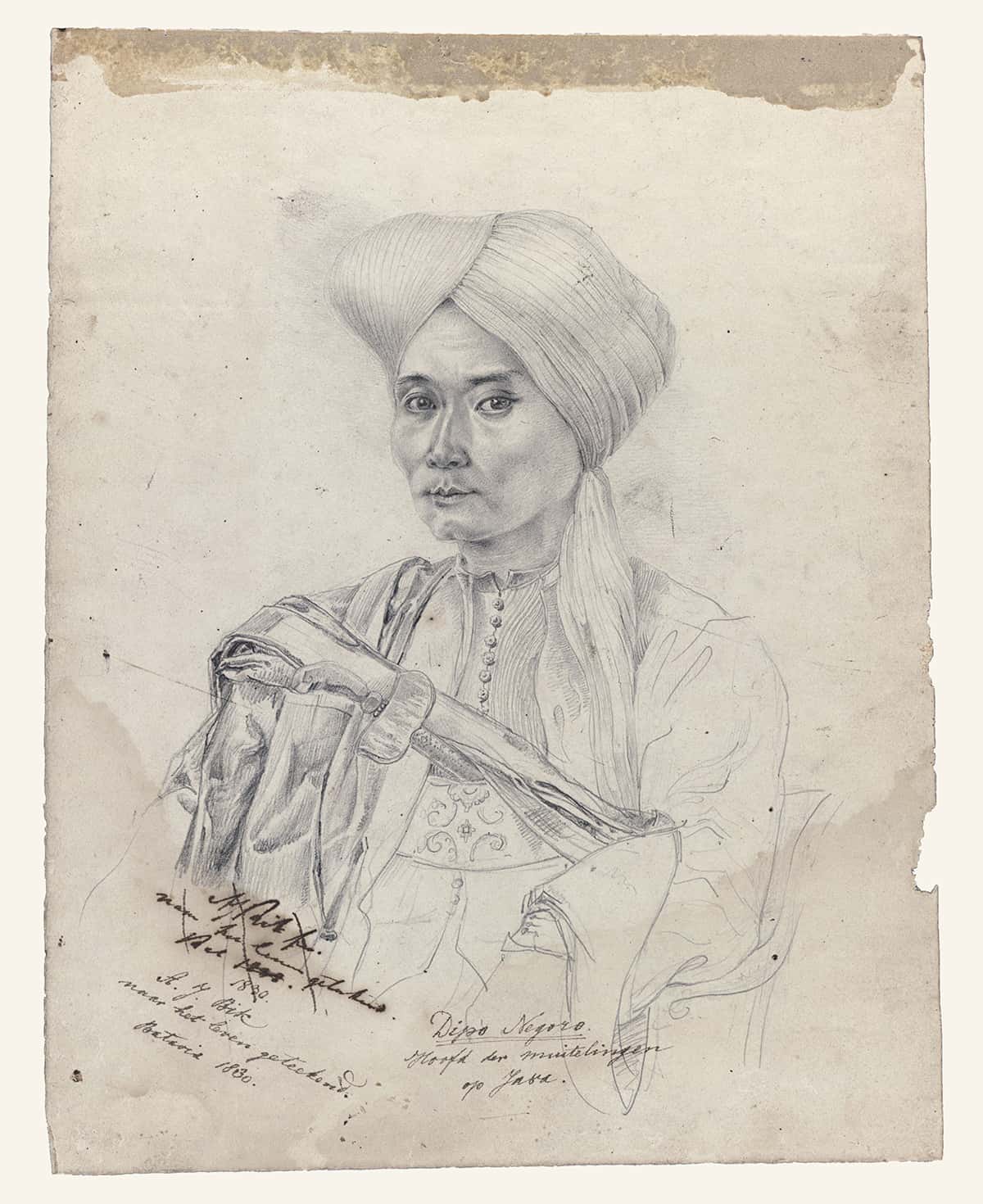

A Rare Portrait and Personal Letters

Adrianus Johannes Bik, a Dutch magistrate and trained portraitist, produced the only live sketch of Diponegoro during his detention in Batavia in April 1830. At that moment, the Prince had just been arrested in Magelang and was being sent into exile. Despite his position as a political prisoner and his emotional trauma, Bik’s drawing captures not only dignity but also serenity. There is a spark in the Prince’s eyes—an expression of humour and unyielding inner strength.

This impression is supported by Diponegoro’s personal letters written at this time. The two extant letters: one to his eldest son, instructing him on safeguarding his family, and one to his mother, assuring her of his well-being while asking for prayers, reveal compassion, resilience, and humility. Both are penned in his distinctive self-taught handwriting. Together with Bik’s sketch, these documents offer a rare glimpse into Diponegoro’s world and the moral strength that defined him.

A Vision for Java

Diponegoro’s vision extended beyond waging war. He imagined Java participating fairly in global trade while safeguarding local values. During negotiations with the Dutch, he offered three pathways to peace: withdrawal on the basis of equal trade, integration through shared faith, or the prospect of long-term Dutch settlement in three north coast cities with coexistence as traders under fair market conditions. Each option reflected not only pragmatism but also moral clarity.

This vision demonstrated his commitment to justice rather than domination. He believed guerrilla resistance could weaken the Dutch to the point of bankruptcy, yet his ultimate goal was not endless conflict but a rebalanced international order rooted in fairness. The treacherous nature of his capture in March 1830, described even by De Kock, the Dutch commander-in-chief, as ‘ignoble’, precluded this possibility.

The Ramifications of Defeat

The Java War was a point of no return. Approximately 200,000 Javanese died, and a third of Java’s six-million population was displaced. Post-war, entire communities uprooted themselves and moved eastward to cultivate new lands in what is now East Java. For the Dutch, victory came at a heavy financial cost but resulted in political and military dominance which was unchallenged until the Japanese military occupation (1942-45). For 112 years after 1830, large-scale armed resistance by the local population on Java was impossible.

The defeat also transformed Javanese aristocratic culture. Princely courts lost their power, and much of their territory was annexed. The remaining elites became dependent on Dutch patronage, serving as administrators and regents. While they retained superficial prestige, their authority was hollow, tied to colonial structures. This hybrid order, conditioned by Dutch norms, created lasting distortions in governance and elite culture.

The Prince’s Inner Transformation

Between his arrest and exile, Diponegoro underwent an important spiritual transition. He moved from amongraga—discipline of the body—to amongrasa—cultivation of inner mindfulness. This shift marked the beginning of his exile years, during which he authored the Babad Diponegoro, and spent his last decade in Fort Rotterdam as a teacher of Sufi Muslim mysticism (guru tasawuf). His acceptance of defeat was not resignation but a profound reorientation towards his Shattari mystical practice and spiritual development aimed at transcendence/knowledge of the sublime (maripat).

Through the Babad Diponegoro, he left behind a vision not just for his time but for generations to come. It is a text that continues to provide a perspective free of colonialism and all traces of colonial mentality, allowing readers to see history not only through the eyes of the colonisers but also through the consciousness of a leader who sought justice, integrity, and spiritual depth.

Lessons for Today: Decolonial Perspectives

Understanding Diponegoro’s life invites reflection on how stories are told and by whom. Colonial history often prioritised European voices, but Diponegoro’s autobiography reclaims narrative agency. His perspective demonstrates that decolonial thinking is not merely about reflecting on the past, but about reimagining how futures might be shaped with dignity and inclusivity.

One important lesson lies in his plural way of thinking. He valued different communities and perspectives, seeking unity across lines of class and faith. For Indonesians today—especially in the diaspora—this serves as a reminder to avoid being too Java-centric in telling national stories. Colonial development in Java focused heavily on Indonesia’s core island, often at the expense of other regions in the outer islands. A decolonial mindset requires decentralising not only economic resources but also cultural recognition, honouring the diversity of the entire archipelago.

Imagining an Alternative Future

Diponegoro’s life allows us to consider what might have been: a Java guided by integrity, justice, and pluralism rather than exploitation and capitalism. His unrealised vision remains a challenge for the present. How can Indonesians today—within the country and abroad—shape futures that are authentic rather than imposed, inclusive rather than centralised?

To answer, one must begin with storytelling. To tell stories truthfully and with dignity is to honour both the hands that create and the minds that imagine. It is also to acknowledge the histories that define identity. By revisiting figures like Diponegoro, Indonesians are not simply looking backward but opening pathways to futures free of exploitation and rich in creativity.

Conclusion: Weaving the Future from the Past

The story of Prince Diponegoro stands at the intersection of past and present, of tradition and transformation. His resilience during the Java War, his vision for a just society, and his writings during exile together offer more than just historical memory; they provide a mirror for contemporary Indonesian society.

For the Indonesian diaspora, the challenge is to weave new rules and stories for today’s generation. Yet, without history, there can be no clarity of direction. Diponegoro’s life shows the importance of grounding the future in values of integrity, compassion, and pluralism. At this simpang masa of our own, his legacy offers both warning and inspiration: a call to build futures