EN / ID

Chapter VI.

Reflections on “Max Havelaar”

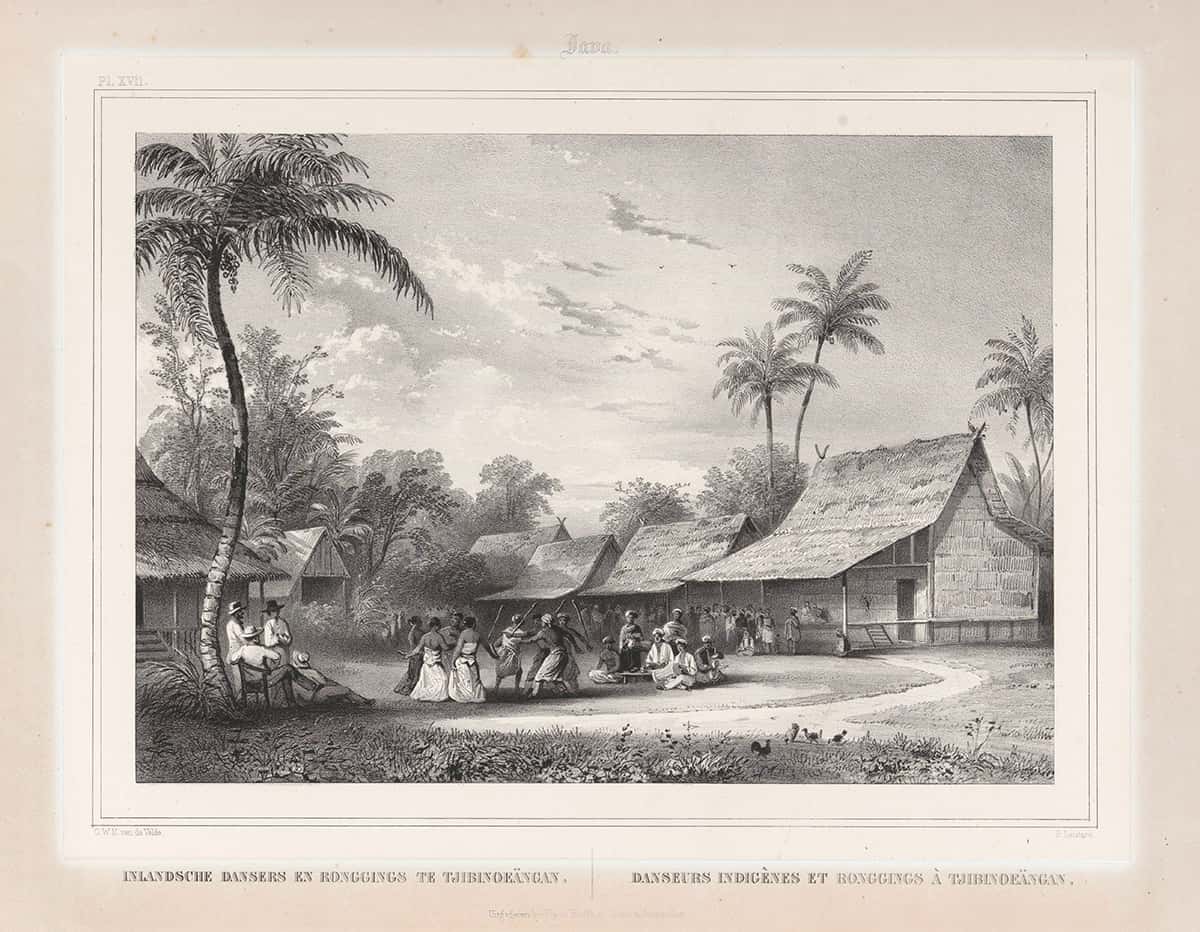

Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker, 1820–1887), a Dutch colonial official turned writer, published Max Havelaar (1860) to expose the systemic corruption of colonial administration and the suffering of the Javanese under the Cultivation System at the height of Dutch colonial rule.

![Multatuli, a Dutch colonial official turned writer, published Max Havelaar to expose the systemic corruption of colonial administration and the suffering of the Javanese under the Cultivation System.]()

In a world where technology and social media allow anyone to broadcast and distort reality, storytelling with integrity becomes an urgent priority. Connecting our personal narratives to cultural heritage is not only an act of preservation but also a path to regeneration for endangered identities. The ego document forms of Babad Diponegoro and Max Havelaar reveal how lived experience can shape collective consciousness. By embracing such models, we may cultivate storytelling that safeguards dignity and opens equitable futures for generations to come.

—Melissa SunjayaThe histories of Max Havelaar and Babad Diponegoro remind us that storytelling can uncover both oppression and resilience. Yet nineteenth-century Java was marked by cultural involution—an inward turn that concealed its once-rich Polynesian heritage, where women had held high honour. Colonialism and rigid conservatism buried these plural traditions, narrowing imagination and marginalising voices. To reclaim them, we must treat ego documents not as relics but as living guides, offering ways to reimagine identity, equity, and cultural regeneration in today’s fragmented world.

—Peter CareyIn 1860, Eduard Douwes Dekker—under the pen name Multatuli—published Max Havelaar. Although presented as a novel, it functioned as a fictional memoir, offering a Dutch colonial officer’s perspective on the corruption and abuses at the heart of the Netherlands Indies government. Its hybrid form, situated between literature and political testimony, allows it to be read alongside Javanese chronicles such as the Babad Diponegoro. While Multatuli’s narrative exposes the empire from within, Diponegoro’s account embodies the voice of a decolonised mind speaking from a Javanese and universalist perspective. Together, these texts highlight the complexity of perspectives in understanding Indonesia’s past and create a space for reflecting on how stories influence histories, policies, and identities.

Ego Documents and Historical Consciousness

The format of Max Havelaar as a fictional ego document highlights the power of subjective narration. Multatuli wrote with urgency and passion, positioning himself as a witness to gross injustice rather than as a detached chronicler. Similarly, Babad Diponegoro—written during the prince’s exile—documents a leader’s vision of resistance, Javanese pre-colonial civilisation, and spirituality. Whereas Multatuli critiques colonial exploitation, Diponegoro articulates a plural way of thinking that sought justice beyond ethnic and regional boundaries. Juxtaposing these two texts illustrates the tension between colonial critique from above and indigenous resistance from below. More importantly, it foregrounds the role of the self in shaping collective memory.

Pluralism and Decentralisation

As a leader, Prince Diponegoro embodied a plural outlook, rooted in his deep spirituality and concern for a just society. This perspective is profoundly relevant to today’s Indonesian diaspora. Too often, national narratives risk becoming Java-centric and narrowly nationalistic, reflecting a colonial legacy in which post-independence development has been concentrated on Java. Decolonial thinking requires a conscious effort to decentralise not only authority but also the economic distribution of opportunities across the archipelago. To tell Indonesia’s story truthfully, we must embrace multiple perspectives—Papuan, Batak, Bugis, Minangkabau, Balinese, and others—ensuring that no region is reduced to the margins. This plural sensibility strengthens our collective identity and offers diaspora communities a framework for understanding their responsibility to represent Indonesia beyond Java alone.

Ethical Policy and Reformative Acts

The publication of Max Havelaar provoked significant debate within the Netherlands. Its stark critique of colonial abuses shattered complacency and pressured policymakers to reconsider their responsibilities towards their colonial subjects. This debate culminated in the early twentieth-century “ethical policy” (1901-1921), which, however limited, signalled an official recognition of moral obligation toward the welfare of the Indies. Programmes for education, infrastructure, and agricultural improvement were initiated under its framework. For the indigenous population, access to education proved particularly transformative. Though uneven and paternalistic, these reforms planted seeds of empowerment that nourished subsequent anti-colonial movements and independence struggles. The ethical policy thus stands as evidence of how personal testimony in literature can translate into institutional change.

The Responsibility of Storytelling

Since colonial times, much of Indonesia’s history has been researched, written about, and preserved by foreign scholars. Many important collections are housed in foreign institutions, which rely on foreign curators to make them accessible to Indonesian scholarship. In March 2019, when the digital copies of the Javanese manuscripts in the British Library were presented to the present Yogyakarta Sultan, Hamengku Buwono X, it was evident that over 200 Javanese manuscripts were in the British Library's possession, at least 75 of which hailed from Yogyakarta. While such historical and curatorial work by foreign experts remains invaluable, it raises fundamental questions of authorship and authority: Who has the right to curate and tell our stories, and from what perspective? To reclaim narrative agency, Indonesians—both at home and in the diaspora—must commit to telling stories with truth and dignity. This entails resisting oversimplification, honouring nuance, and acknowledging traumatic histories. Moreover, the same ethic must also inform the creative economy. Storytelling, whether through literature, craft, or design, should nurture rather than exploit. It should honour the hands that make, the minds that imagine, and the histories that define us. A decolonial creative economy demands ecosystems of care, not systems of extraction.

Diaspora and the Future

For Indonesians living abroad, the challenge is twofold: to remain connected to heritage while articulating contemporary identities. The diaspora must weave its own rules and narratives, drawing from plural traditions rather than singular centres. Yet without knowledge of history, planning for the future becomes nearly impossible. The lessons of Max Havelaar and Babad Diponegoro remind us that storytelling is not merely a record of the past—it is a foundation for action to reform the present. By revisiting colonial critiques and indigenous resistance, diaspora Indonesians can craft narratives that are honest, inclusive, and forward-looking.

Conclusion: Max Havelaar, weaving stories, instilling dignity

Max Havelaar illustrates how literature, framed as an ego document, can expose systemic injustice and ignite reform. Babad Diponegoro, by contrast, reveals how a decolonised consciousness can articulate plural visions of justice. Together, these texts highlight the importance of perspective in shaping histories and futures. For Indonesia today, particularly its diaspora, the responsibility lies in decentralising narratives, reclaiming authorship, and ensuring that creative economies foster dignity rather than exploitation. To plan a meaningful future, we must first understand and retell our histories—not only those written by outsiders, but also those we write for ourselves. Only then can we weave a story of Indonesia that honours its plurality and prepares future generations for governance.