EN / ID

Chapter IV.

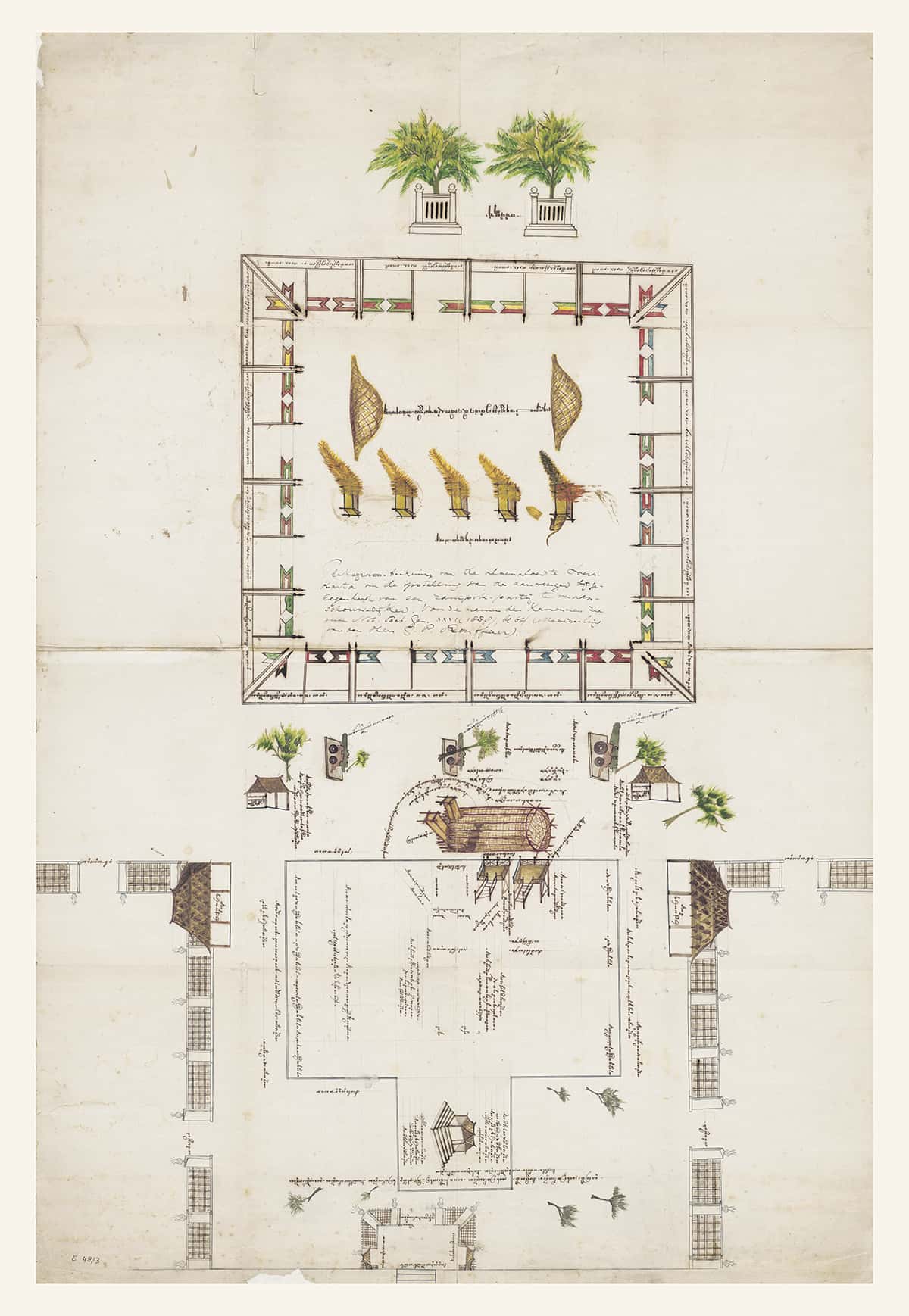

Rampogan Macan

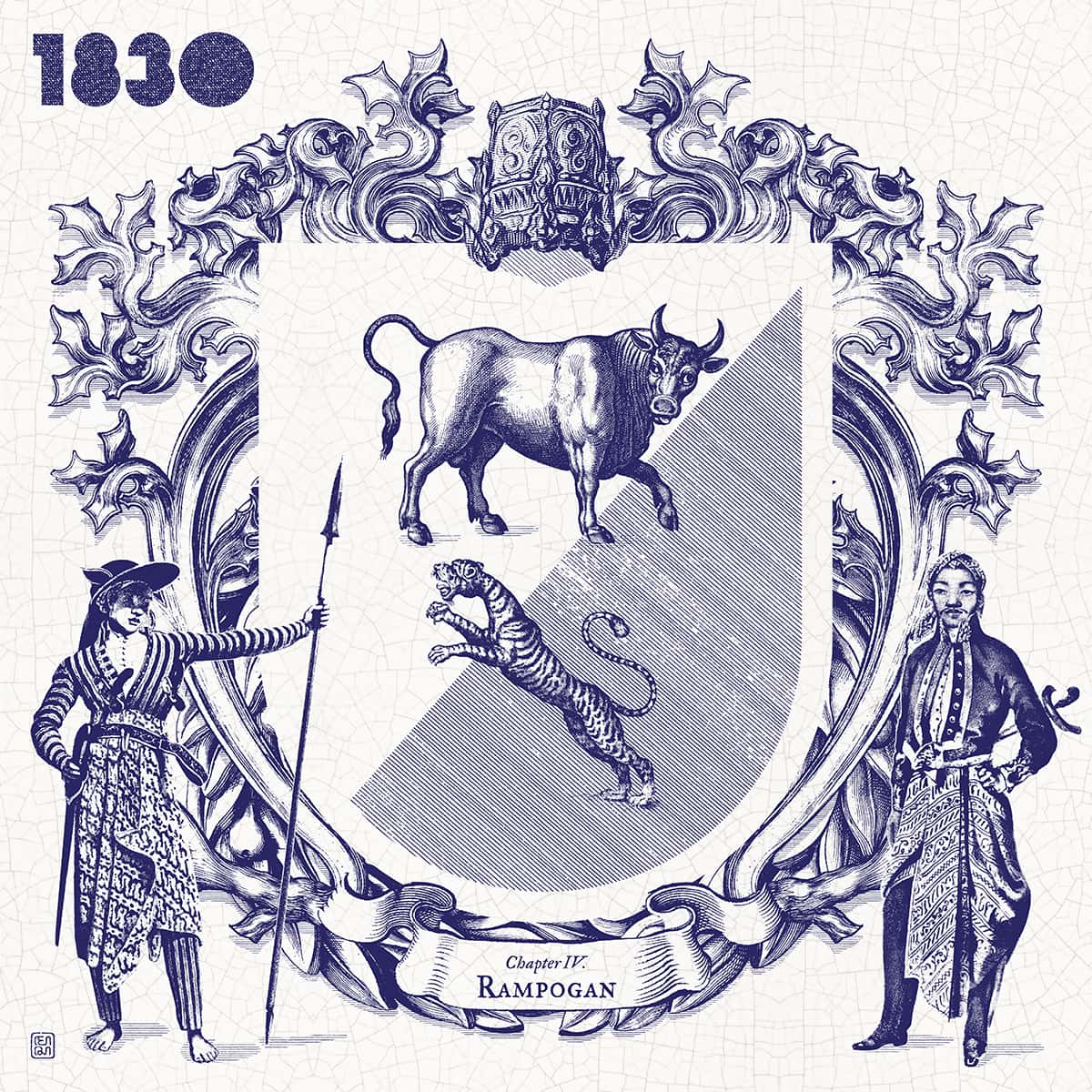

This heraldic emblem depicts a rampogan, a ritual fight between buffalo and tiger once staged by the courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta. Symbolising resilience and spiritual power, the practice ended in 1862 and was banned by the Dutch in 1905.

Whether we realise it or not, we all carry symbols that shape who we are. In Java, woven textiles have long been more than fabric—they are stories of ancestry and identity. Just like national emblems, these symbols help us express what we believe, share our views, and connect with others who see the world as we do. They remind us that identity is not only personal but also collective, giving us both purpose and belonging.

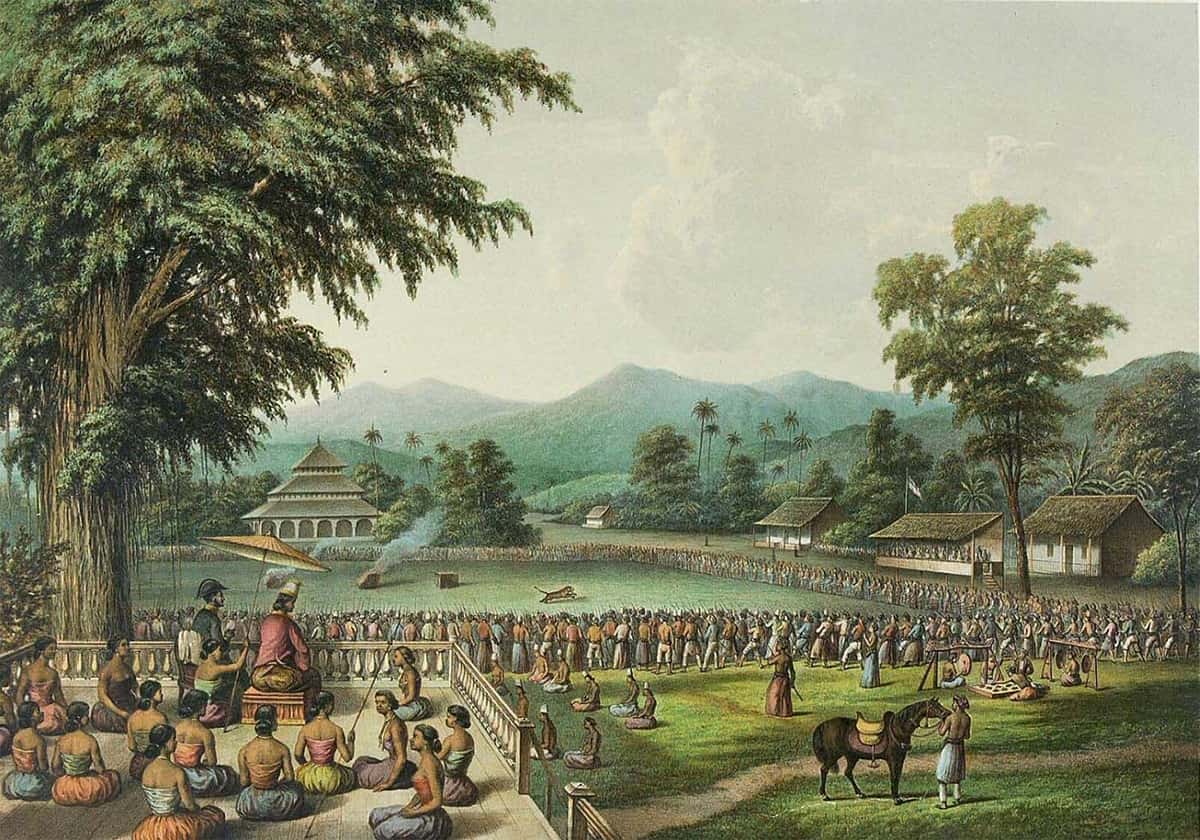

—Melissa SunjayaThe rampogan stood as a marker of Java’s ancien régime, reflecting the deep connection between the Javanese elite and the natural world. In Java’s Old Order, satria lelono (wandering knights) embarked on spiritual journeys through a countryside imbued with magic and meaning. This intimacy with nature sustained a centuries-old cultural identity. Colonial rule, however, brought mapping, surveys, and capitalist exploitation. What Max Weber termed the “disenchantment of the world” replaced rasa (intuitive feeling) and intuition, transforming lived experience and consigning practices like the rampogan to history.

—Peter CareySigns, Symbols, and Identity

Since independence was declared on 17 August 1945, Indonesians have continually asked: how should a nation visually express its identity? Symbols remain central to this question. Names, emblems, attire, tattoos, or even consumer brands are ways in which people align themselves with communities and beliefs. Such symbols may affirm belonging, but they also reveal how power is expressed through tradition, clothing, and visual culture.

In the Indonesian case, many of these cultural identifiers were disrupted or reshaped under colonial rule. Whereas pre-colonial traditions reflected close relationships with the natural and spiritual worlds, colonial authorities recast indigenous visual culture into mere decorative or symbolic forms, stripping them of their inner philosophical meaning.

Rampogan: Rituals of Power and Nature

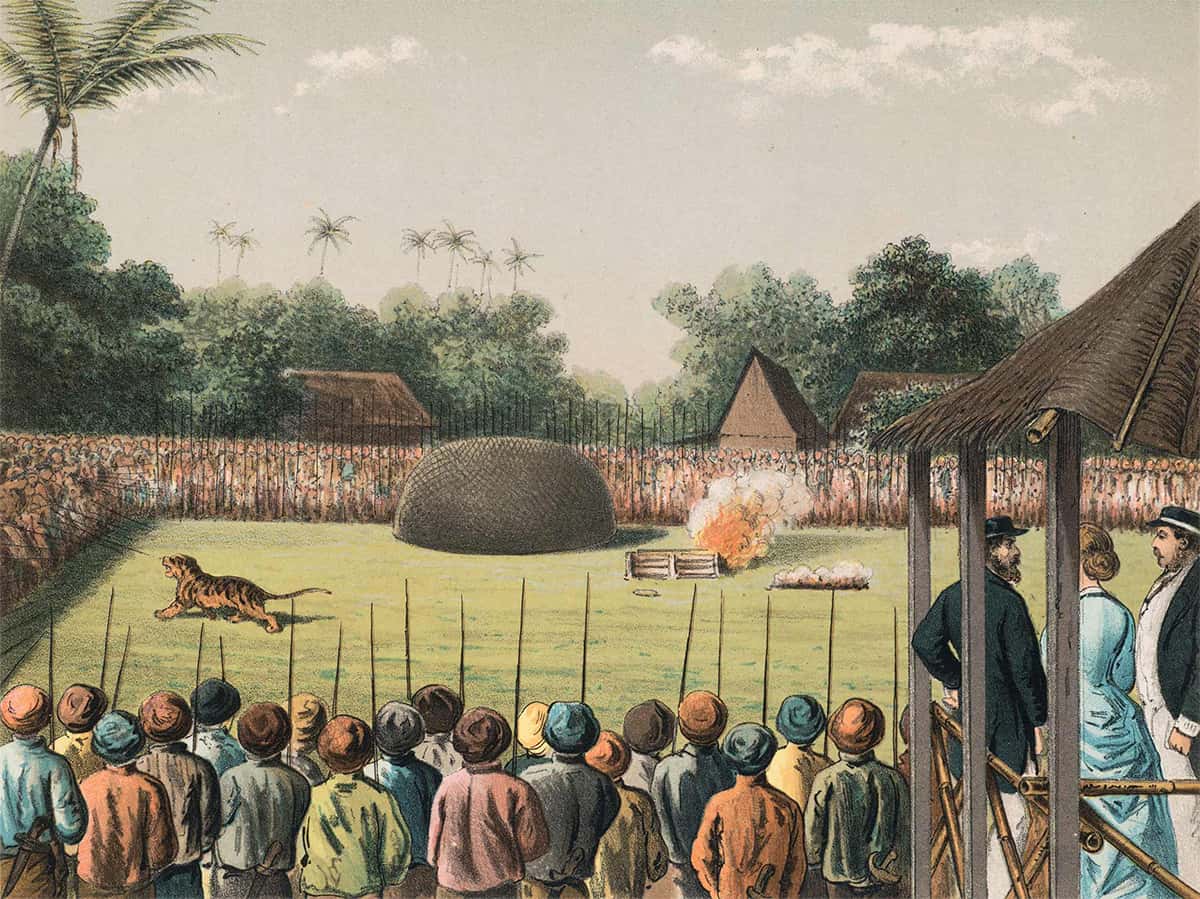

The fate of the rampogan illustrates this fading of cultural identity. More than an exotic spectacle for visiting Europeans, it was a ritual of power dynamics. The buffalo and tiger symbolised a cosmic drama: patience and resilience overcoming cunning and ferocity. Hundreds of Javanese pikemen, positioned with spears around the arena, enacted a choreography of courage, discipline, and spiritual strength. At its core, the ritual affirmed that Javanese rulers and their people lived in deep connection with the natural world, physically and spiritually.

Such rituals underscored that Javanese culture was not timid, calm, or submissive, as colonial narratives would later suggest. This ancient culture was bold, enchanted, and resilient. Yet with colonial bans and changing values, the rampogan disappeared, leaving only fragments of symbolism, its underlying philosophy fading from collective memory. What remains today are echoes—reminders of a worldview where nature, ritual, and identity were inseparable.

From Enchantment to Disenchantment

The colonial regime not only outlawed practices like the rampogan but also introduced new modes of seeing and ordering the world. Forests once regarded as sacred were surveyed, mapped, and measured for economic exploitation. What was previously an enchanted landscape, imbued with ancestral power, became a rationalised commodity. With this transformation, rituals that once embodied living philosophies were relegated to decorative performance.

The German sociologist Max Weber spoke of “disenchantment”. In Java, this process unfolded with stunning speed: a spiritual landscape of intuition and feeling gave way to the calculative gaze of colonial capitalism within a couple of decades (1808-1830). Pre-colonial ways of knowing—rasa (intuitive feeling), ritualised discipline, spiritual resilience—were undermined by imported models of rationalisation. The loss was not only of ritual but also of an entire worldview.

Colonial Visual Culture and Its Legacy

The rampogan also draws attention to how visual culture itself was reshaped under colonial rule. Heraldic emblems—derived from European monarchies—entered Javanese courts through alliances with the Dutch. The Yogyakarta palace emblem, for instance, reflects this borrowing, with echoes of the Dutch royal coat of arms. Over time, such symbols displaced indigenous cosmologies like the Surya Majapahit, reducing ancestral visual systems to mere ornament.

Many of the Javanese traditions and visual markers familiar today are, in fact, products of this colonial encounter. They embody a hybridised culture where pre-colonial philosophies were either silenced or reinterpreted through European frameworks. This raises an urgent question for the present: how can new generations detect what has been lost, and how might new cultural rules be created to address the absence of pre-colonial traditions?

Reclaiming Ritual and Meaning

The banning of the rampogan exemplifies the broader colonial strategy of neutralising indigenous expressions of power. What had once been a profound enactment of courage and resilience became an outlawed memory, the surviving rituals emptied of meaning and relegated to the symbolic. Yet within the imagery of the buffalo and tiger lies a subversive narrative: the endurance of Javanese patience and strength, and the eventual evaporation of colonial ferocity.

To reclaim such meanings is not to revive lost spectacles but to rediscover the philosophies they embodied. Pre-colonial societies articulated power, resilience, and identity through close relationships with nature, rituals of balance, and cosmologies of interconnectedness. These were not primitive practices, but sophisticated systems of thought with enduring relevance, to be honoured and celebrated, not discarded and rendered irrelevant.

Conclusion: Detecting Absences, Creating Futures

The rampogan reminds us that colonialism not only imposed political control but also restructured culture, aesthetics, and identity. It shifted visual culture from lived philosophy to surface symbol, creating gaps in memory and understanding. For Indonesians today, especially the younger generation, the task is to develop new ways of detecting these absences—of asking where philosophy has been replaced by decoration, and where rituals have been drained of meaning.

In Java and the surrounding islands, ancestral knowledge and philosophy have long been transmitted through the materiality of textiles, clothing, and rituals. These objects embody meaning not only in their decorative forms, but also in how they are sourced, crafted, and used. Such practices sustain and harmonise the relationship between humanity and nature. In this sense, the Babad Diponegoro also offers an authentic framework for an empathetic model of living.

Through understanding such texts, it becomes possible to create new cultural rules: ones that honour the boldness of our Javanese ancestors, revalue the interconnectedness of humans and nature, and restore dignity to traditions once dismissed as mere spectacle. The rampogan, though long vanished, continues to provoke questions about how power is expressed and culture reshaped. In brief, how the stories of the past might guide the identities of the future.