EN / ID

Chapter II.

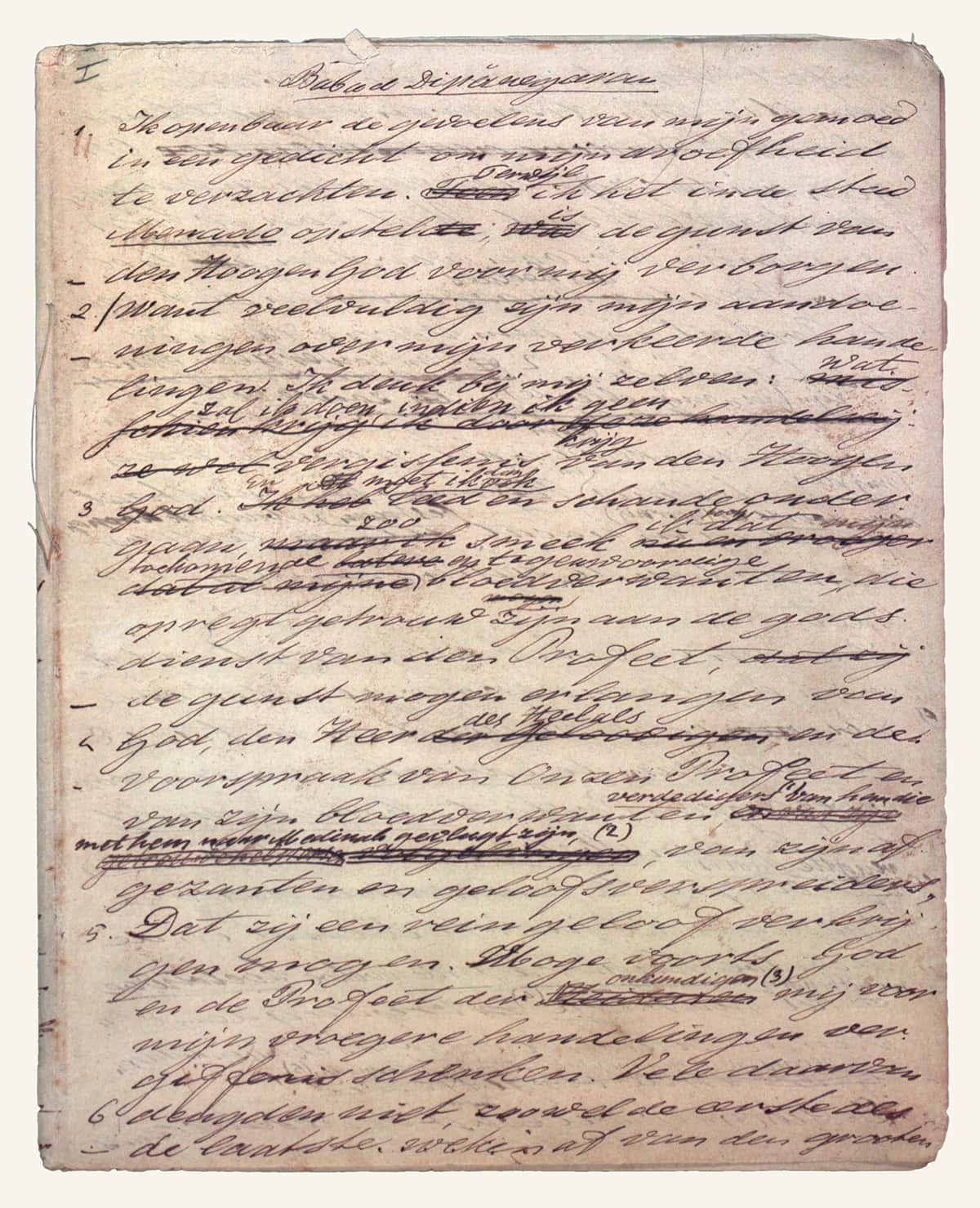

Babad Diponegoro

The three-masted Dutch Corvette-of-war Pollux (1824–38) transported Prince Diponegoro to exile in Manado in May 1830. Less than a year later, within the walls of Fort Nieuw Amsterdam in the North Sulawesi capital, the prince began to compose his literary masterpiece, Babad Diponegoro.

![The three-masted Dutch Corvette-of-war Pollux transported Prince Diponegoro to exile in Manado in May 1830.]()

Babad Diponegoro is one of the earliest Javanese autobiographies and a cornerstone of Indonesian literature. Recognised by UNESCO as a Memory of the World manuscript in 2013, it remains little known beyond scholarly circles. Accessible editions and accurate translations are lacking. The 1830 project takes an interdisciplinary approach to reframe this masterpiece, bringing Diponegoro’s vision into contemporary objects and daily life. His “wisdom of a simple man” shows a path to authenticity and freedom from colonial influence.

—Melissa Sunjaya

Reading the Babad Diponegoro in the original Javanese is like sitting face-to-face with the prince himself. His words draw you onto the sofa in the Resident’s office in Magelang on that fateful Sunday, 28 March 1830, as De Kock informs him he will not return to his encampment at Meteseh. Such vivid encounters reveal the richness of this extraordinary autobiography. Recognised by UNESCO as a Memory of the World, it deserves a bilingual critical edition accessible to all Indonesians.

—Peter CareyThe Contents and Style of the Babad

Babad Diponegoro is both autobiography and chronicle. Written in Javanese macapat verse and dictated to an unknown writer assistant over nine months between May 1831 and February 1832, it recounts the history of Java from the fall of Majapahit through to Diponegoro’s own lifetime and his leadership in the Java War. The first cantos retell centuries of Javanese history, providing context for the disunity and colonial interference that shaped Diponegoro’s world. The later sections are deeply personal, tracing his childhood outside Yogyakarta, his spiritual journeys, and his reflections on justice, morality, and leadership.

The prince’s style is distinctive. Rather than adopting the detached tone of official chronicles, he employs a conversational voice infused with humour, sarcasm, and sharp observation. He describes human quirks with wit—recounting, for instance, a widow and herbalist who treated him for fever—or narrating tense encounters with Dutch commanders-in-chief with a mix of irony and restraint. His storytelling is immersive, allowing the reader to feel as though the prince is seated across from them, speaking directly. This intimacy makes the Babad unique: it is both literature and life testimony, crafted with poetic cadence yet grounded in everyday detail.

Purpose of Writing

Diponegoro’s initial purpose was clear: he wished to leave a record for his family, especially his children born in exile, so they would grow up with knowledge of their Javanese heritage. The Babad was a gift across generations, a way to preserve values, beliefs, and lessons in the face of displacement and cultural erosion.

At the same time, the Babad was also a political act. By narrating his version of events, Diponegoro reclaimed the authority to interpret his own struggle rather than leaving the story to Dutch official historians or court chroniclers dependent on the colonial power. In this sense, the Babad was a decolonial statement long before the term existed.

Reflecting on his purpose allows comparison with today’s lives under global capitalism. Just as Diponegoro resisted narratives imposed by colonial rule, individuals today struggle against the homogenising pressures of consumerism and economic exploitation. Many live under systems that value productivity over dignity and profit over culture. The Babad encourages readers to ask: how do we preserve integrity, cultural identity, and values of care when living under such massive external constraints?

Relevance for Today

The Babad Diponegoro is more than a historical document; it can serve as a framework for reflecting on contemporary Indonesia. Its emphasis on moral leadership, social tolerance, and just governance resonates with current struggles against corruption, inequality, and economic injustice.

In terms of identity, the Babad reconnects readers with pre-colonial traditions largely obscured by later hybrid cultures. It affirms that Indonesian identity is not solely a colonial inheritance but rooted in much deeper indigenous values. Socially, it presents a vision of human relationships based on empathy, spiritual depth, respect for diversity and transcendence. Politically, it foregrounds integrity and accountable leadership. Economically, it reminds us of Diponegoro’s insistence on fair trade, rejecting exploitation and demanding justice. Spiritually, it underscores our inner worth.

For the younger generation, the Babad offers lessons on resilience, authenticity, and pride in our cultural heritage. It presents a way of life grounded on local wisdom and pluralist values thus freeing us from colonial inferiority complexes. Reading it today can help Indonesians imagine futures that are not shaped solely by global capitalism but also by ancestral values of fairness and care.

Personality Through Writing

Diponegoro’s character emerges vividly through his writing. He was disciplined yet humorous, deeply spiritual yet practical. His tone alternates between sharp critique of injustice and wry reflection on human frailty. His self-taught handwriting, couched in lyrical macapat poetic form, underscores a personality that valued both discipline and creativity.

The prince’s humility shines through in moments when he admits to failure or contemplates his own fate. Yet his dignity remains unshaken. He chose not to end his life in chaotic violence when captured, reasoning that posterity would remember him better for restraint than for rash defiance. Such reasoning reveals a leader who thought not only about his own honour but also about his long-term reputation in the eye of eternity.

In this way, the Babad is a portrait of character: a man who balanced courage with reflection, severity with humour, conviction with compassion.

Autobiography and Social Media

The Babad can be seen as an early form of ego document—an autobiography shaped by its author’s voice, values, and context. In this sense, it invites comparison with how people today use social media to broadcast their lives online. Both are means of self-presentation, ways of shaping how one is remembered and perceived.

Yet there is a key difference. Social media often fragments identity, presenting curated snapshots driven by algorithms and external validation. The Babad, by contrast, is holistic. It integrates personal history, cultural memory, political struggle, and spiritual reflection into a coherent narrative. Where social media rewards immediacy and spectacle, the Babad prioritises sincerity, patience, depth and cogitation.

This contrast invites reflection: how might today’s digital generation move beyond fleeting self-display to more meaningful self-narration? Can the act of telling one’s story become not just performance, but also preservation of values and identity? In this sense, Babad Diponegoro is not only a text from the past but also a guide for navigating storytelling in the present and future.

Conclusion: The meaning of the Babad Diponegoro

Written in exile, Babad Diponegoro is both a personal testimony and a cultural monument. Its contents combine history, autobiography and poetry, articulated through a distinctive voice that remains strikingly modern. Its original purpose—preserving heritage for his descendants—extends into the present as a reminder for all Indonesians to reclaim their narratives from external powers, whether colonial or capitalist.

As a framework for today, the Babad affirms identity, social cohesion, political integrity, and economic justice. It reveals Diponegoro’s personality as a leader who combined humour, humility, and vision. It also offers a compelling contrast to contemporary practices of self-narration, challenging us to tell our stories with authenticity and depth.

Ultimately, the Babad is a conversation across centuries. It asks: have we done enough to understand ourselves? By engaging with Diponegoro’s text, Indonesians and the wider world are reminded that authentic identity is not found in imposed narratives or the fleeting fashion of the ‘trending’, but in values rooted in history, memory, and the courage to imagine futures free from external domination.