EN / ID

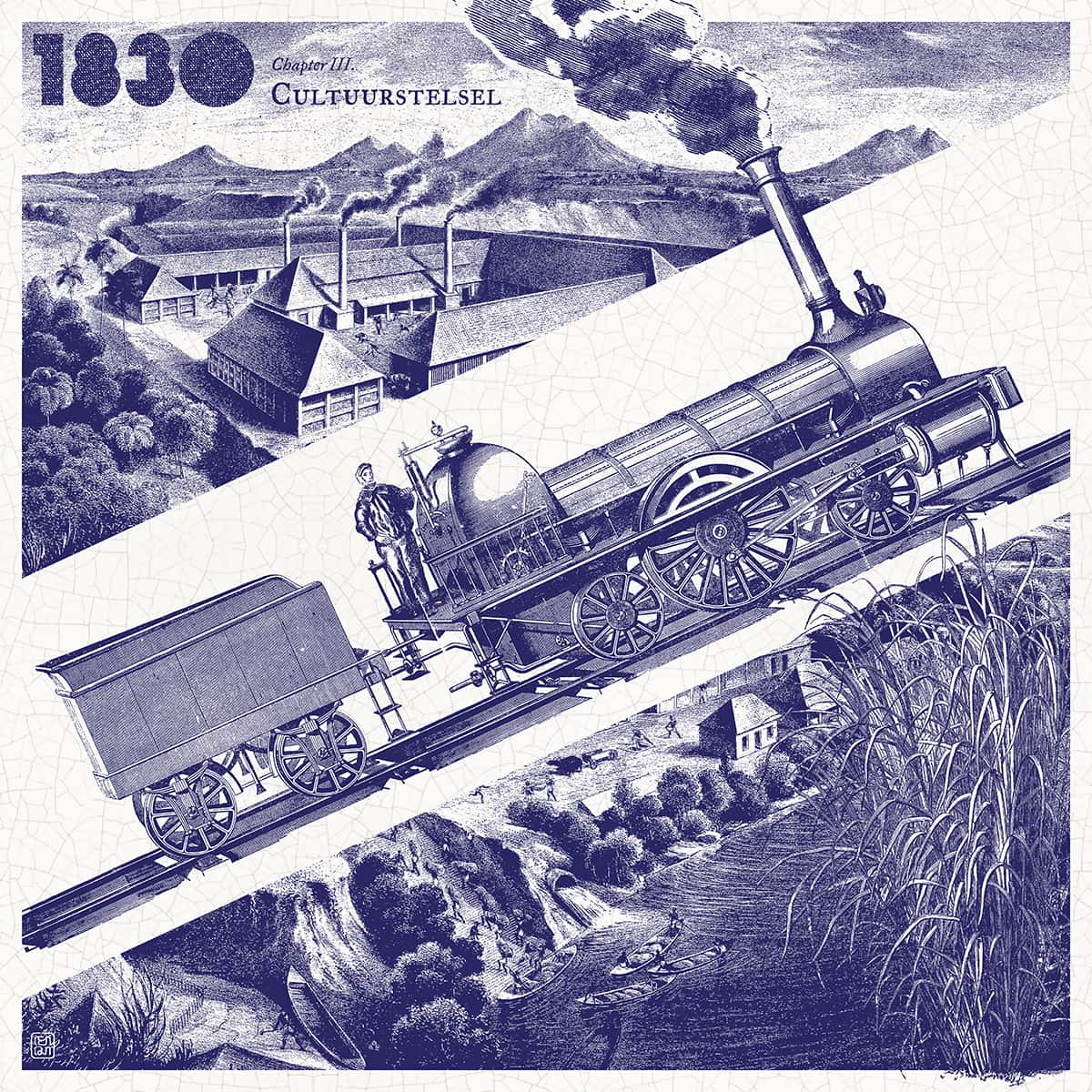

Chapter III.

Cultuurstelsel

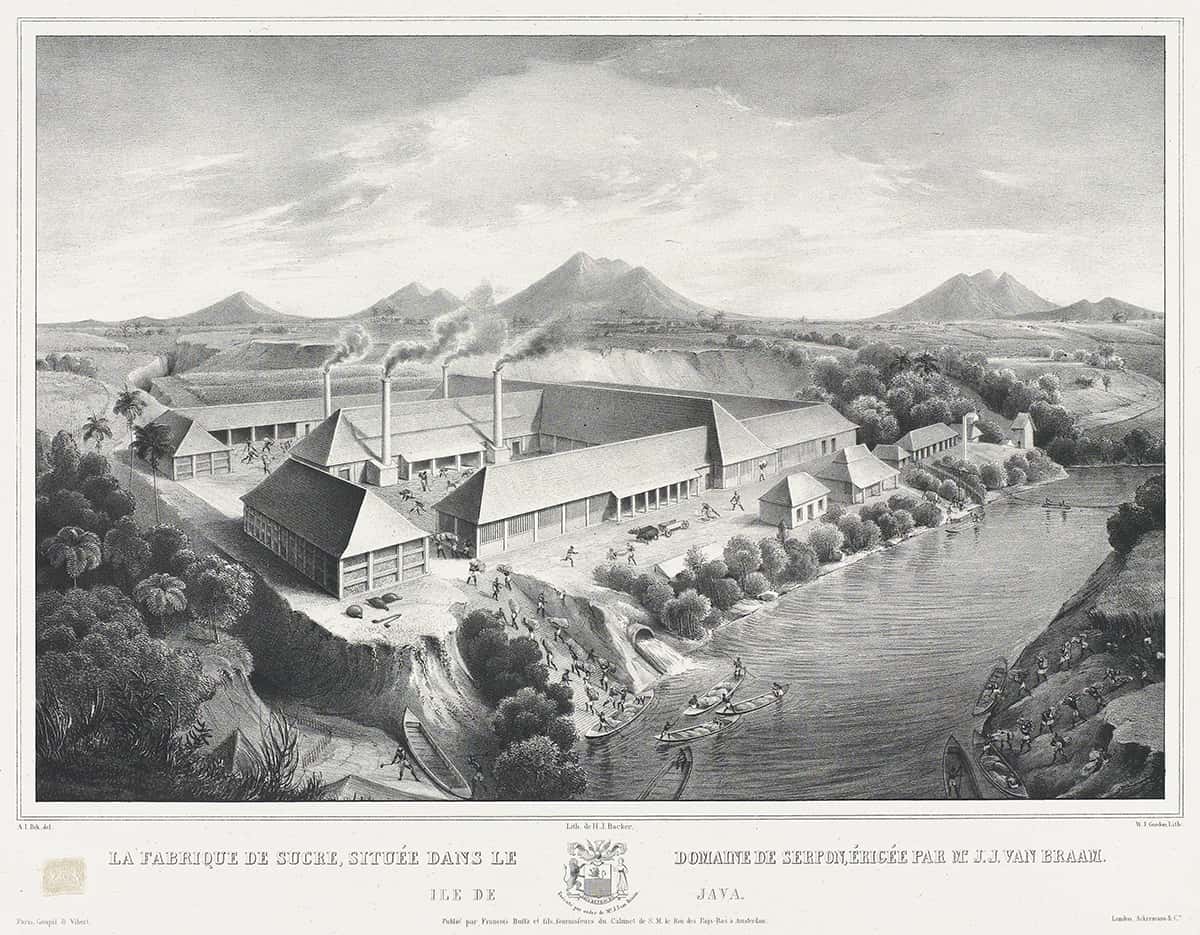

This sugar mill on the banks of the Kali Cisadane in Serpong and the construction of the railway are among the many radical changes that reshaped Java’s landscape and culture under the Cultivation System (1830-70) initiated by Governor-General Johannes van den Bosch.

![This sugar mill in Serpong and the railway construction are among the many radical changes that reshaped Java’s landscape and culture under the Cultivation System.]()

My first taste of coffee was not Javanese kopi tubruk but an Italian espresso—ironically brewed with beans from Java. Years later, as a consultant for consumer brands, I discovered that nearly one-third of international cargo entering Europe and America originates in Indonesia. Made in Indonesia products are everywhere, yet our nation remains little recognised. This dissonance reflects a systemic injustice rooted in the 1830 Cultuurstelsel, which stripped commodities of their cultural origins, rebranding them instead as colonial goods.

—Melissa Sunjaya

The Cultuurstelsel was the nadir of Dutch colonialism in Java. Between 1830 and 1870 it yielded 832 million guilders—about USD 11 trillion in today’s money—while impoverishing the island’s people. Famines and epidemics swept Java as Dutch coffers overflowed; at one point the system supplied over a third of Holland’s public revenue. Contemporary voices exposed this injustice: Raden Saleh lamented that polite society spoke only of “coffee and sugar,” while Multatuli’s Max Havelaar (1860) burned with outrage, shaming a complacent Dutch public.

—Peter CareyCoffee, Sugar, and the Bitter Truth

In mid-nineteenth-century Europe, sugar, coffee, tea, cinnamon, and indigo were coveted luxuries. These products, exported from Java by the Dutch Trading Company or VOC, became essential to Western consumer life. They were no longer ‘exotic’ rarities but part of the bourgeois household—served in salons, woven into upholstery, painted onto porcelain, and steeped in everyday rituals. This trend was also known as “chinoiserie” which gave birth to the “Delft blue” industry.

Yet behind the refinement of Delft blue ceramics or the global popularity of a “cup of Java” lay a system of forced labour. Farmers in Java were compelled to cultivate export crops under fixed prices that guaranteed vast profits for the Dutch colonisers but impoverishment for local producers. Between 1830 and 1870, this system—the Cultuurstelsel—drained wealth from Java and funnelled it into the industrial transformation of the Netherlands and other European countries.

Why the Cultivation System Was Established

The Java War (1825–30) had left the colonial treasury nearly bankrupt. The Dutch state faced debts of 20 million guilders, and the Dutch Trading Company (NHM) struggled against British and American competition. King Willem I, himself a principal NHM shareholder, needed a rapid solution.

Johannes van den Bosch proposed one: the Cultuurstelsel. Introduced in 1830, it required Javanese farmers to surrender one-fifth of their rice fields and perform 66 days of unpaid labour annually. These obligations produced sugar, coffee, indigo, and other crops for the global export market. The system quickly stabilised Dutch finances. Within a few years, debts were cleared, and the Dutch crown reaped massive surpluses—profits extracted not from Dutch soil but from Javanese ricefields.

How the System Worked on the Ground

In theory, regulations protected farmers by limiting land use and guaranteeing compensation. In practice, corruption and coercion ruled. Farmers often lost access to more than the stipulated one-fifth of their fields, while delays in harvesting or crop failures brought punishments and extra labour demands.

A striking example came from the mid-19th-century in Demak and Rembang, where sugar and indigo cultivation left insufficient land for rice. Famines followed, and many villagers died of starvation. In Tegal, workers were forced to transport sugarcane manually over long distances to factories because of inadequate infrastructure, such as roads and railways. While European consumers enjoyed cheap sugar, Javanese peasants paid for it in blood and suffering.

Beyond Java, the pattern repeated elsewhere. Indigo farmers in Bengal, India, and West Africa also faced coercion and ruin under similar colonial schemes. Their crops supplied European textiles, wallpaper, and porcelain, while producers remained trapped in cycles of debt and poverty. The suffering of Javanese peasants was part of a global chain of exploitation that enriched European industries at the expense of colonised populations.

The system also sharpened social divisions. The priyayi, or Javanese elite, became intermediaries of colonial rule. Once traditional leaders, they were transformed into bureaucrats with privileges tied to their loyalty. The toiling farmers, meanwhile, became captive labourers, losing both economic independence and cultural autonomy.

Profits for the Dutch Colonisers

The financial gains were extraordinary. Between 1831 and 1877, the Dutch treasury received 832 million guilders (equivalent to over US$100 billion in today’s currency). At its peak, Cultuurstelsel profits made up over a third of state revenue.

These revenues fuelled industrialisation in the Netherlands—funding canals, railways, and modern infrastructure—while little was reinvested in Java. The Dutch colonisers ensured that wealth flowed one way: outward. Even the currency system, established in the Dutch East Indies, worked against local producers, as copper coins minted in Europe circulated at a devalued rate against silver in Java.

For the colonisers, the system was a triumph. For Java, it spelt poverty and dependency.

Lasting Social and Cultural Impacts

The Cultuurstelsel not only exploited labour; it also reshaped culture and communication. Under colonial surveillance and censorship, open criticism spelt death, imprisonment and exile. Over time, Javanese society developed a careful, euphemistic way of speaking. The blunt defiance of figures like Prince Diponegoro gave way to coded messages, metaphors and innuendo.

This cautious mode of communication became deeply ingrained. To avoid punishment or loss of status, criticism was often disguised through layered language, proverbs (pantun), or symbolic gestures. Even today, traces of this legacy can be seen in the reluctance to speak directly on controversial issues, reflecting how colonial structures continue to shape everyday interaction and cultural norms.

The ecological consequences were equally severe. Forests were cleared for plantations, railways, and factories, transforming Java’s landscape into an agri-business export production area. By the late colonial period, population pressure, environmental degradation, and agricultural overexploitation left lasting scars on both land and livelihoods.

From Cultivation System to Capitalist Precepts

Understanding the Cultuurstelsel reveals more than colonial history; it highlights how global capitalism continues to mirror these dynamics. The structural inequality—where producers in the Global South receive the least while global brands cream the profits—remains strikingly contemporary.

For instance, many Indonesian artisans and small producers today still operate under consignment systems in shopping centres, where payments are delayed for months and margins are heavily skewed in favour of retailers. These arrangements echo the colonial practice of delayed payments and undervaluation, effectively binding local producers to cycles of precarity.

Similarly, global commodity chains still impose fixed pricing on raw materials—whether coffee beans, palm oil, or cocoa—leaving farmers vulnerable while profits accumulate at the processing and branding stages, usually abroad. This logic, developed under colonial precepts, still underpins neoliberal trade structures: wealth is centralised, risk is localised, and those who work the hardest are often those who benefit the least.

Conclusion: Learning from the Past to Shape the Future

Cultuurstelsel, connections emerge between nineteenth-century colonial exploitation and today’s inequities in global trade. The lessons are sobering: wealth can be built on systemic impoverishment, and consumer pleasures often mask unseen suffering.

Yet, this understanding also offers an opportunity. If colonial policies created extractive economies, contemporary societies can imagine more ethical alternatives. By valuing local producers, ensuring fair payment, and nurturing sustainable practices, new economic models can be designed that decentralise opportunity beyond Java and extend dignity to those who work with their hands and creative imaginations.

The Cultuurstelsel’s history is not just a chapter in the past but a mirror to the present. Recognising its legacy opens the possibility of a different future—one that does not repeat the injustices of the past but learns to grow and transcend them.